Practically speaking, there are tremendous differences between carburetors designed for various automobile models. In addition, the linkages, assist devices, and various controls on all carburetors can vary widely, even between two automobiles of the same make and model but with different engines. Yet all carburetors work on the same basic priciples.

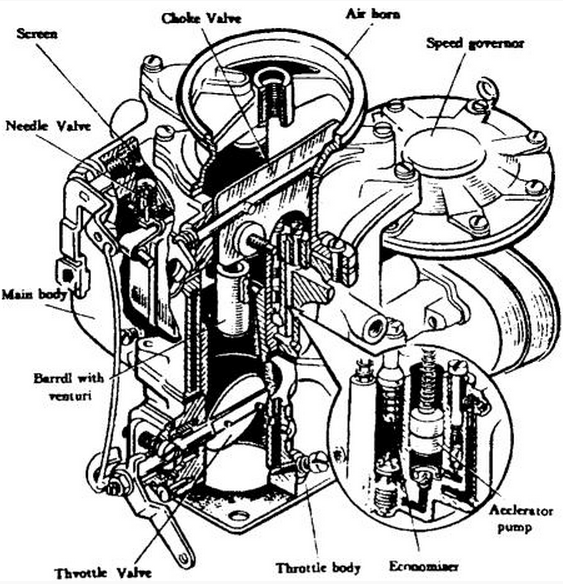

A carburetor is a metering device that mixes fuel with air in the correct proportion and delivers this mixture to the intake manifold, where it delivers the air/fuel mixture to the various combustion chambers. Metering, in this situation, means that components within the carburetor accurately measure and control the flow of fuel and air passing through the various carburetor systems (Fig. 10).

The engine must have some form of metering device when its source of fuel for power is gasoline. In a liquid state, gasoline is of very little use to the engine. Contrary to popular belief, gasoline in a liquid is not combustible only gasoline vapor burns. Therefore, the carburetor or another metering device must combine the gasoline properly with the correct amount of air in order for the combustion process to release the energy in the gasoline.

|

| Fig. 10 The carburettor of autombile |

The function of any carburer found on a gasoline engine is to meter, automize, and distribute the fuel through the air flow passing into the engine. The carburetor is designed in such a way that it carries out all of these functions automatically over a wide range of operating conditions such as varying engine speeds, loads, and operating temperatures.

The carburetor also must regulate the amount of this air/fuel mixture that flows into the intake manifold. This regulation gives the driver the necessary control of the speed (rpm) of the engine.

Good combustion requires the correct mixture ratio between the air and fuel-commonly known as the air/fuel ratio. This ratio is necessary for the combustion process to release all the possible energy contained in the gasoline. An excessive proportion of fuel in the ratio results in a “rich” mixture; whereas, too little fuel bring about a ”lean” mixture. The metering task of any carburetor then is to furnish the correct air/fuel ratio for all operating conditions, so that the operation of the engine is not excessively lean to meet its power requirements or too rich for economy while still meeting the prime requirements of low emission.

The carburetor must not only meter the amounts of air and fuel entering the engine but also atomize the fuel. Atomization simply means the breakdown of the liquid into very small droplets of particles so that it can easily mix with air and vaporize. As the carburetor breaks the fuel into these small droplets, this action permits additional air contact with the liquid fuel. The greater the air contact, the easier the fuel turn into a vapor inside the intake manifold.

For excellent combustion and smooth engine operation, the carburetor must thoroughly mix the air and fuel together, and the intake manifold must uniformly distribute this mixture in equal quantities to all the engine’s combustion chambers. Adequate distribution of the mixture requires good vaporization. Vaporization is the act of changing a liquid, such as gasoline, into a gas, this change of state only occurs when the liquid absorbs sufficient heat to boil.

Because complete vaporization is the result of many factors such as outside air temperatures, fuel temperature, manifold vacuum, and intake manifold temperatures, it should be quite apparent that anything that reduces any one of these factors will adversely alter the vaporization process and therefore reduce engine power and fuel economy plus increase harmful exhaust emissions. Some of the conditions that interfere with proper vaporization are cold weather, inoperative heat-riser valve, high overlap camshaft, and heavy throttle demands.

The carburetor must provide an air/fuel mixture within the range of 8:1 and 18.5:1 in order for an engine to run. For the sake of efficiency, the engine should utilize a ratio that produces peak power output, minimum emission, and peak fuel economy. Unfortunately, no single air/fuel ratio permits an engine to meet all these conditions. Tests have proven that the best engine power output comes from using a 12.5 to 13.5:1 mixture; whereas, the best fuel economy results from using a 15, 16:1 mixture. Since no singe fuel ratio is satisfactory, the carburetor must quickly match the varying engine load requirements with the best possible air/fuel mixture in order to achieve the most efficient operating conditions. This simply means that the carburetor not only must provide a ratio to meet power demands, caused by such things as light-speed variations and changing engine load conditions, but also provide reasonable fuel economy and minimum exhaust emissions.

One of the main reason why the carburettor must vary the air/fuel ratios is the imperfect conditions within the combustion chambers. For example, exhaust gases remaining in the combustion chamber dilute the incoming fresh air/fuel charge. In addition, there are timed when the carburetor does not properly mix the air and fuel together. As result, tiny droplets of unvaporized fuel move into the combustion chamber, carrying along by the mixture of air and evaporated fuel. Finally, the intake manifold itself does not always deliver equal air/fuel mixture to all the cylinders.

No comments:

Post a Comment